French troops slaughtering Spanish civilians in Goya’s painting “The Third of May 1808”.

Why are some beings indifferent to the sufferings of other beings if there is soul-kinship among all beings?

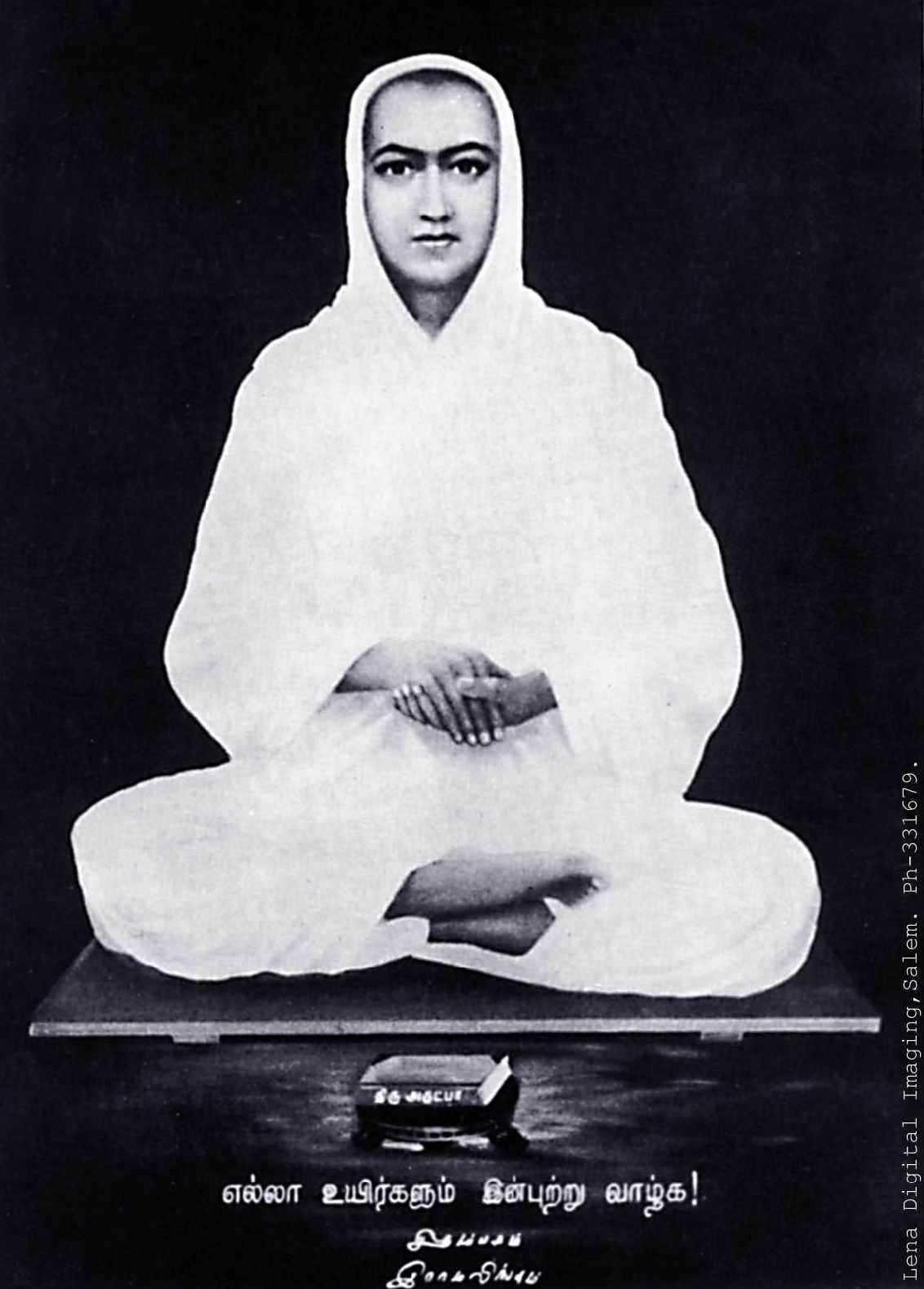

Ramalingam raises this important question in his great unfinished essay on ஜீவகாருண்ய ஒழுக்கம் or “The Ethic of Compassion for Sentient Beings“.

He answers by pointing out that although soul-kinship is a reality, the central faculty of discernment (Tamil: ஆன்ம அறிவு) of this truth of soul-kinship is obscured or eclipsed by ignorance in some beings.

This cardinal ignorance also renders the soul’s cognitive instruments of mind, intellect, etc., opaque and unable to reflect the light of the truth of soul-kinship.

Hence, these beings do not recognize soul-kinship, and, consequently, lack compassion for other sentient beings who undergo suffering. From this it follows that those who have compassion possess the faculty of discernment of soul-kinship.

As Ramalingam writes in Tamil in the first part of his essay on compassion for sentient beings:

“சீவர்கள் துக்கப் படுகின்றதைக் கண்டபோதும், சிலர் சீவகாருணியமில்லாமல் கடினசித்தர்களாயிருக்கின்றார்கள்;

“Some persons lack compassion and remain unmoved even at the sight of the suffering of other sentient beings.”

இவர்களுக்குச் சகோதர உரிமை இல்லாமற்போவது ஏனெனில்:–

“Why do these persons lack a sense of brotherhood or kinship (with those sentient beings)?”

துக்கப்படுகின்றவரைத் தமது சகோதரரென்றும் துக்கப்படுகின்றாரென்றும் துக்கப்படுவாரென்றும் அறியத்தக்க ஆன்ம அறிவு என்கிற கண்ணானது அஞ்ஞானகாசத்தால் மிகவும் ஒளி மழுங்கினபடியாலும், அவைகளுக்கு உபகாரமாகக் கொண்ட மனம் முதலான உபநயனங்களாகிய கண்ணாடிகளும் பிரகாச பிரதிபலிதமில்லாமல் தடிப்புள்ளவைகளாக இருந்த படியாலும் கண்டறியக் கூடாமையாயிற்று.

“It is because their faculty of soul-knowing (ஆன்ம அறிவு ), the soul’s eye, which can see that another sentient being which is suffering is a brother, or kin, and that it is suffering, or is capable of suffering, is afflicted by the cataract of ignorance, and, consequently, even the spectacles or instruments which facilitate the vision of the soul, e.g., mind, intellect, etc., are rendered opaque and bereft of the capacity to reflect the light of knowledge (of soul-kinship).”

அதனால், சகோதர உரிமையிருந்தும் சீவகாருணியம் உண்டாகாம லிருந்ததென் றறிய வேண்டும்.

“Hence, they lack compassion despite the fact of their brotherhood or kinship with those sentient beings.”

இதனால் சீவகாருணியமுள்ளவர் ஆன்ம திருஷ்டி விளக்கமுள்ளவரென்றறியப்படும்.” (ஜீவகாருண்ய ஒழுக்கம், முதற் பிரிவு)

“From this, it should be known that those who have compassion possess the clarity of vision of the soul’s eye of discernment, or soul-knowing.”

Thus, in Ramalingam’s analysis, there is fundamentally an epistemic or cognitive deficiency, the eclipse of the soul’s central faculty of discernment (ஆன்ம அறிவு), which is responsible for the absence of compassion in the face of suffering experienced by other sentient beings.

In a Socratic vein, Ramalingam holds that the cardinal vice of absence of compassion is due to lack of knowledge of the truth of soul-kinship.

But if each soul has this faculty of discernment which enables it to recognize soul-kinship with another sentient being, why does this faculty get obscured, eclipsed, or atrophied, due to ignorance, in some souls or beings? In other words, why are some beings afflicted by this ignorance of their soul-kinship with other sentient beings?

To answer this question, we must turn to the concept of āṇavam (Tamil: ஆணவம்), or egoism in the Tamil Saiva Siddhanta tradition.

Although he had a deep knowledge of it, Ramalingam was not an adherent or practitioner of the Tamil Saiva Siddhanta philosophical tradition. But he does affirm some of its metaphysical claims.

A central metaphysical claim of this tradition is that all unenlightened souls or pašu (Tamil: பசு) are fettered by the three cords of bondage or pācam (Tamil: பாசம்): ஆணவம் or āṇavam (egoism), கன்மம் or kaṉmam (karma, causality), and மாயை or māyai (matter, the “stuff” of our bodies and cosmos).

Ramalingam affirms this claim in his definition of the unenlightened soul or pašu (பசு) in his “Ethic of Compassion for Sentient Beings”.

Aṇavam is the primordial impurity (Tamil:ஆணவமலம்) which taints every individual soul in the form of a potentiality. It is manifested in terms of a tendency toward a separate, selfish, and exclusive existence. It leads to an eclipse of a soul’s ability to recognize soul-kinship.

As a consequence, there is an exacerbation of the division between self and the other. This division further paves the way to opposition, conflict, enmity, domination, and oppression in its relations with other beings and the inevitable chain reactions of Karma which assail the soul.

Thus, we can only explain the absence of compassion in some beings in terms of their ignorance of soul-kinship. Their ignorance of soul-kinship, in its turn, is explained by their longstanding choice of cultivation of the separative and exclusive tendencies of āṇavam or egoism and their subjection to the inevitable karma or consequences of these egoistic tendencies.

Hence, to recover and develop this knowledge of soul-unity or soul-kinship we must reverse the process of ignorance in question by weakening the tendencies of āṇavam or egoism and cultivating empathy and compassion.

It is interesting to note that Wang Yang-Ming also holds the view that the innate sense of unity with all things, the innate knowledge that the myriad things form “one body”, can be 0bscured by selfish desires, a manifestation of āṇavam, and that this obscuration can lead to cruelty against others:

“This means that even the mind of the small man necessarily has the humanity that forms one body with all. Such a mind is rooted in his Heaven-endowed nature, and is naturally intelligent, clear, and not beclouded. For this reason it is called the “clear character.”

Although the mind of the small man is divided and narrow, yet his humanity that forms one body can remain free from darkness to this degree. This is due to the fact that his mind has not yet been aroused by desires and obscured by selfishness.

When it is aroused by desires and obscured by selfishness, compelled by greed for gain and fear of harm, and stirred by anger, he will destroy things, kill members of his own species, and will do everything.

In extreme cases he will even slaughter his own brothers, and the humanity that forms one body will disappear completely.

Hence, if it is not obscured by selfish desires, even the mind of the small man has the humanity that forms one body with all as does the mind of the great man. As soon as it is obscured by selfish desires, even the mind of the great man will be divided and narrow like that of the small man.

The learning of the great man consists entirely in getting rid of the obscuration of selfish desires in order by his own efforts to make manifest his clear character, so as to restore the condition of forming one body with Heaven, Earth, and the myriad things, a condition that is originally so, that is all.” ( “An Inquiry on the Great Learning,” in A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, translated and compiled by Wing-Tsit Chan [Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963], pp. 659-660.)

There is an interesting objection to Ramalingam’s argument that discernment of soul-kinship is the basis of compassion and that, therefore, lack of compassion is due to the lack of discernment of soul-kinship.

This objection points to those who do not subscribe to the notion that there is a soul, not to mention soul-kinship, but who are, nevertheless, compassionate.

Does the existence of these sorts of compassionate persons refute Ramalingam’s argument linking compassion and discernment of soul-kinship?

The answer to this objection must first clarify what Ramalingam means by “discernment of soul-kinship”. This discernment is a function of a cognitive faculty (Tamil: ஆன்ம அறிவு) possessed by a soul. The Tamil term used by Ramalingam to refer to this faculty means “soul-knowing” or “soul-discernment”.

What sort of knowledge is discernment of soul-kinship?

It is the knowledge that other sentient beings, regardless of their physical forms or bodies, are, nevertheless, beings similar to me in that they can suffer and be subjected to various types of harm, or flourish, in the way I can.

It is the knowledge that other sentient beings are selves, or subjects of experiences, and agents with varying capacities for action, in the way I am.

It is also the knowledge that by virtue of these similarities, a bond, or relation, or kinship, exists among us and that, as a consequence, I have an obligation to provide assistance or relief to these sentient beings if I know that they are undergoing suffering or harm and possess the capacity to alleviate their suffering or harm.

(I would add, in this context, that all scientific knowledge of the similarities and common origin of sentient beings can facilitate the discernment of soul-kinship with all those beings.)

Now, it cannot be denied that compassion is constituted by an empathetic understanding of the nature and predicament of another sentient being, an understanding which has all the elements of Ramalingam’s concept of discernment of soul-kinship.

Therefore, those who are compassionate possess this type of empathetic understanding of other sentient beings, or discernment of soul-kinship, and it does not matter whether they actually use the concept of soul-kinship and its discernment in describing their understanding.

Regardless of the vocabulary employed by these compassionate persons to describe the elements of their empathetic understanding, it is tantamount to a discernment of soul-kinship.